One day, the writer and lawyer Deirdre Mask was lost somewhere in West Virginia. She had borrowed her father's car to drive to the home of an acquaintance, equipped with complicated directions. What made it particularly difficult was that the man she intended to visit had no address. His street lacked a name, and his house had no number.

As Mask would discover, many residents in that West Virginia county were in a similar situation. They'd pick up their mail at the post office. And if directions were required, they'd talk of landmarks instead: turn at the stone church, go past the factory, left at the drive-in restaurant, and so on.

So over many years, West Virginia has been making a state-wide effort to name its unmarked roads. Often the titles have been chosen by officials: reflecting local history, for instance. But as Mask discovered, in a few places residents have proposed eclectic titles such as Booger Hollow, Crunchy Granola Lane or even Stupid Way. Some have been happy to take on names, but many have not, feeling they reflect a form of governmental oversight they don't want or need. (The resident who suggested Stupid Way did so "because this whole street name stuff is stupid".)

In a few places, residents lobbied for Booger Hollow, Crunchy Granola Lane or even Stupid Way

Stories like West Virginia's inspired Mask to take a closer look at street names all over the world. How and why have people chosen the ones they have? It's easy to take for granted that roads have titles, but look a little closer and they can reveal a great deal about the nature and character of a place, as well as its history. "We think of street addresses as purely functional and administrative tools, but they tell a grander narrative of how power has shifted and stretched over the centuries," she writes in The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal about Identity, Race, Wealth, and Power.

In recent years, Mask and others have converged on the idea that if you want to gain a deeper understanding of a place – its defining culture and underlying attitudes – you should look at the titles it has chosen for its roads, alleys and boulevards. It's an approach that one group of researchers is now calling "streetonomics" – and it promises to uncover previously hidden insights about the societies we live within.

McDowell County in West Virginia: where the streets have no name (Credit: Katherine Frey/Getty Images)

How does a street get its name? Perhaps it's based on its location or a landmark: Main Street, Market Lane, Orchard Road. It could be called after a place: Oxford, Massachusetts, Atlantic. It might be a person: Victoria or Jefferson. Or simply a utilitarian number, from Fifth Avenue to 42nd Street. (The most common street name in the US is not a founding father or other historical icon: it's actually "Second".)

In the long view of human history, though, street names are a relatively recent invention. What tends to be forgotten today is that the practice of street titling emerged for more complex reasons than exchanging post or visiting people. "When we think of addresses, it's that they're useful to get our packages delivered, or to navigate around, but they actually weren't designed for us. They were designed for the state," explains Mask.

Centuries ago, governments realised that naming the streets allowed centralised oversight of their citizens, be it for drafting into the military, taxation, or to verify who somebody was. That hasn't changed much. As the world has become complex, your home address remains a key part of your identity in the eyes of governments, banks and other officialdom. It's required on almost every form you fill out, and every job, document or loan you apply for – which is why it's such a struggle for those who don't have one.

But that's not the only way that the state has leveraged street names as an extension of their power and influence. "Since the beginning of time, rulers have used spatial engineering as a form of social engineering," write Melanie Bancilhon of Washington University in St Louis and colleagues at Nokia Bell Labs in Cambridge UK in a paper published in June. "As a result, street names mirror a city’s social, cultural, political, and even religious values."

You may also like:

- Do you want to help build a happier city?

- How your name affects your personality

- What the sound of your name says about you

A few hundred years ago, political leaders began to realise that they could use street naming to preserve memories of their military victories, societal legacies, venerated figures, and political ideologies. But these values differ by location. In London, some streets are linked to the Royal Family, avenues of Washington DC are named after the member states of the Union, while streets in once-socialist Bucharest celebrate the working class. In some cases, street-naming serves as a deliberate attempt to rewrite history. For example, in South Africa during the apartheid period, place names originated by the fusion of European and Afrikaans names, which served the interests of colonial powers.

Bancilhon and colleagues were curious about whether it might be possible to quantify some of these societal values, by comparing the naming approach in different places. The inspiration came from some of their previous work, which BBC Future first covered back in 2013, where they attempted to measure aspects of a city not captured by the usual economic indicators, such as how people attach emotions and memories to certain places. They were also inspired by the study of "culturomics", which attempts to study previously unquantifiable facets of human culture.

A street in a suburb of Vienna, one of the cities that the "streetonomics" team studied (Credit: Joe Klamar/Getty Images)

So, they pioneered a new approach that they called "streetonomics". To demonstrate how it works, they studied the patterns within 4,932 streets in Paris, Vienna, London and New York, cities chosen for their cultural influence in the Western world (as well as accessible data).

The first thing they were able to see was when street naming had accelerated in each of the four cities. For example, London named a lot of its streets during the decades following the Great Fire of 1666, while Paris went on a spree between 1850-1870 as the city centre was redesigned.

For New York, however, naming has been much more recent. It may be famous for its numbered streets, such as Fifth Avenue, but in recent decades, many have been co-named with honorific titles, especially after 9/11. Mask has observed this pattern too, pointing out that in recent years some 40% of all local laws passed by New York City Council have been street name changes. In 2018 alone, it co-named 164 streets.

Gender biases

Once the streetonomics team had built their database, they were able to see other patterns too. Street names, they found, can have a gender bias – and this differed between the four cities. In Paris, only 32% of the streets named after people were female, while in New York City, its recent naming spree has done little to skew a bias towards men, with only 26% of its person-titled streets honouring women.

"Despite Paris and New York being centres of progressive culture, they still fail to commemorate men and women in equal measure. Sadly, what is a historical legacy will stay with us in the future, if these two cities do not change their course," the researchers write.

Paris, to its credit, has taken some steps towards reversing its gender inbalance. Following political campaigns from groups such as OsezLeFeminisme, in 2015, Paris Mayor Anne Hildalgo decided to rename several streets after women such as Nina Simone, Assia Djabar, Simone de Beauvoir, and Rosa Parks.

London fares a little better, with women making up 40% of streets carrying people's names. But Vienna offers the model of how to evolve with the times. In the 1880s, the percentage of Viennese person-titled streets named after women was below 5%, but since the 1980s, many streets have been renamed, bringing the total to 54%.

Of person-titled streets in Paris, male names (green) are more common than female (purple) (Credit: Social Dynamics/Nokia Bell Labs)

...whereas in London, streets named after people are 60% male and 40% female (Credit: Social Dynamics/Nokia Bell Labs)

Other trends that the streetonomics team observed included changes in the types of professions venerated. Certain jobs have been consistently celebrated over the centuries, such as artists and writers – particularly so in Paris and Vienna – but others have gone out of fashion, such as military leaders. In recent decades, London has begun to name more streets after people in the creative sector than one its previous favourite sources: the Royal Family. And in New York, most of the named streets come from the "business and community" sector, such as civil servants, or emergency responders involved in the 2001 attacks.

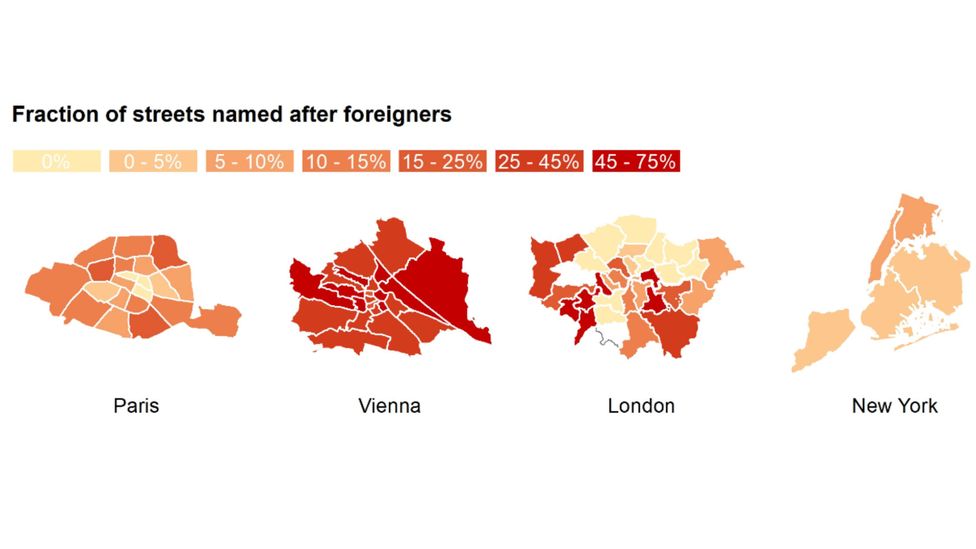

The researchers also found that some city leaders have been more willing than others to name their streets after foreigners. Among the four they studied, Vienna has shown the greatest willingness to celebrate nations other than its own, with 45% of streets named after non-Austrians. Contrast that with New York, which only has 3%, clustered mainly in the Bronx.

"New York is the very model of a global city, but it is more so financially than culturally," write the researchers. "That might be partly because the city is quite young compared to Vienna or Paris, and partly because it tends to focus on itself."

New York seems to have been the least willing to name streets after foreigners (Credit: Social Dynamics/Nokia Bell Labs)

For Mask, street names also speak to aspects of a place and people that are harder to quantify with data: in particular, attitudes about race – and how that has changed (or not) over time.

To illustrate what she means, she tells a story about a controversial street she came across while house-hunting in Tottenham, London. With a small budget, she and her husband had been pleased to find a potential place with wooden floors and bay windows that had just come on to the market – but when they visited, they discovered a problem that was impossible to ignore.

"The street was tidy, and I saw potential neighbours clipping hedges and planting flowers in their front yards," she writes. "At one end of the road was a friendly looking pub; on the other end, a grand-looking state school with a garden classroom and swimming pool… The house sat squarely in the most diverse postcode in the United Kingdom, and probably all of Europe."

On the surface, it had everything going for it. "I did really like it. But I had a nagging problem: could I really live on Black Boy Lane?"

Mask, a black American, couldn't get past the idea that this would be her address. While it's unclear how the street got its name, the words "Black Boy" reminded of a condescending slur used in her home country, as well as the UK's colonial history in the slave trade. She and her husband decided to pass.

The local council has since opened a consultation with residents about renaming the street, but for now, it's still there. The discussion has followed much of the same patterns as recent debate over controversial statues. For some, the street name is history and so should stay, while for others, it's outdated and offensive.

Nearly 900 streets in the US are named after Martin Luther King (Credit: Getty Images)

Debates over street names can be a bellwether for a culture's underlying attitudes, says Mask. In her book, she explores the politics and perceptions surrounding a common street title in her home country: Martin Luther King, whose name can be found on nearly 900 addresses in the US. "It can actually tell you a lot about race in America", she says. Road signs carrying the name of the civil rights activist are often vandalised. And there remain negative perceptions about the communities living and working on these streets.

"The comedian Chris Rock once joked that if you find yourself on Martin Luther King street, then run, because these are dangerous places," says Mask. "Now that's not always true, and in fact, some studies have found that MLK streets aren't necessarily poorer than other ones – Main streets or JFK streets – but they're different. They have more churches and more schools, for example."

Sadly, Martin Luther King's name on an address influences how some people see the commerce and community there, no matter how safe and liveable the neighbourhood is. "Because they're so connected with blackness, people see them as bad, even if they aren't really bad," says Mask.

Whether you like it or not, the name of the street you live on matters. In 2015, research by the real estate company Zillow found that houses on named streets in the US are often worth more than numbered streets – and in the case of Los Angeles or San Francisco, by more than 20%. Properties on streets with less common names also tend to be more valuable: one of the lowest value addresses to live on is Main Street.

Naming alternatives

So, in the 21st Century, might it be time to reconsider street names? Given all the controversy they attract and the unequal historical power dynamics they reflect, might we look to other approaches? After all, digital technology allows for it.

Mask points out that there are already alternatives – what3words, for instance, a proprietary system that assigns a random string of words to a location. For example, to find the entrance to BBC's Broadcasting House in London, you don't need its street name, you could just plot a route to "daring.begins.these" (or the less glamorously-named adjacent spots, "jumps.slugs.bulbs" or "fried.dairy.worker").

But while Mask acknowledges that digital addresses would bypass the controversies, she wouldn't replace the conventions we have. "People don’t always unite around street names… But I like the arguments. Arguments are what divide communities, but they are also what constitutes them as communities.”

So, the next time you walk around your neighbourhood or city, take a closer look at the street signs you see – they might tell you a lot more about where you live than you might realise.